“Give unto Caesar what is Caesar’s and unto God what is God’s.” I’m not sure how many times I’ve seen those words pop up on Facebook over the past few years. Typically it comes as a dismissive defense against any serious attempt to wrestle with the entanglement of faith and politics. It compartmentalizes the two, putting politics in one box and faith in another.

But is that was Jesus is saying? Is Jesus suggesting that we have distinct spiritual, social, political, and work lives? Or have we taken a couple verses from a much larger story and incorrectly applied it to a single context?

Compartmentalization is easy to embrace when you look at how popular Western Christianity thinks about what God is doing in the world. If God is, as I propose, simply in the business of judging and redeeming, and the church is solely in the business of announcing redemption through Jesus, then faith and everyday life have little to do with one another beyond the sins that offend a holy God. From that position it is very easy to embrace the popular understanding of, “Give unto Caesar what is Caesar’s, and unto God what is God’s.”

But again, is that what Jesus suggests? To find that answer, we should begin by looking at the surrounding context of, “Give unto Caesar.”

Setting the Stage

Mark sets the context for the exchange between Jesus and the religious leaders on Tuesday of Holy Week:

Again they came to Jerusalem. As he was walking in the temple, the chief priests, the scribes, and the elders came to him and said, ‘“By what authority are you doing these things? Who gave you this authority to do them?”

Mark 11:27-28, NRSV

What are these things that they refer to? According to Mark, two days earlier Jesus rode into Jerusalem on a donkey and the day before he flipped over tables in the temple. Clearly the chief priests, scribes, and elders saw these actions as significant, but how would they have understood them?

The Imperial Parade

This was no ordinary Sunday in Jerusalem. No Sunday before Passover could ever be a regular Sunday. Five days from now, at sunset, Jewish people from all over the known world would sit down to a meal and tell the story of how God rescued them from four-hundred years of Egyptian slavery. But the story is always present tense. Yes, the event first happened over a thousand years ago, but Passover always happens in the present. It is happening today. Right now. Here. For us.

But if that is true, it is dangerous. If we really believe God is actively bringing us out of bondage on this Passover through the death of our oppressors‘ first born, what does that mean for the Roman guards walking the street as the people eat and relive the story? These are the very same guards whose march caused the ground to shake on this Sunday before Passover as they processed into Jerusalem.

Their arrival that morning serves as a reminder that while they permit the Jews to hold the Passover festival, they are anything but free. Their march still echos through the streets. The rumble, a terrifying promise to crush any threat to Emperor Tiberius Caesar‘s Pax Romana. Emperor Tiberius Caesar, who calls himself the “son of God,” “lord” and “savior.” The Pax Romana created by a sword to bring “peace on earth.”

The Last Anti-Imperial Parade

Two-hundred years ago the Jews could consider themselves free. It came with the procession of the victorious Simon Maccabaeus riding into Jerusalem. The crowd, celebrating liberation, met him “with praise and palm branches” (1 Maccabaeus 13:51). His triumphal entry took him from outside the city to the temple where he cleansed it, reestablishing traditional Jewish worship.

But while Simon’s victory parade always came to mind this time of year, today the resonance is stronger. Because on this Sunday, there were two processions. As the heavily armed Roman guard with an earth shaking march and clanging spears entered one end of the city, a second less gaudy procession took place, one that brought questions and a complex blend of excitement, anticipation, and abject terror. The procession centered on Jesus of Nazareth, an itinerant preacher and miracle worker.

Jesus‘ Anti-Imperial Parade

The contrasting images and memories stirred up by Jesus’ parade fueled the diversity of reactions to his arrival. Like the rebel Simon Maccabaeus, he rode into town with praise and palm branches. But rather than riding in on a war horse with an army, Jesus came on a donkey embodying the anti-militaristic liberation of the prophet Zechariah.

Rejoice greatly, O daughter Zion! Shout aloud, O daughter Jerusalem! Lo, your king comes to you; triumphant and victorious is he, humble and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey. He will cut off the chariot from Ephraim and the war-horse from Jerusalem; and the battle bow shall be cut off, and he shall command peace to the nations; his dominion shall be from sea to sea, and from the River to the ends of the earth.

Zechariah 9:9–10, NRSV

Adding one more level of complexity to the scene, the crowd that at Jesus‘ entry gathered shouted, among other things, “Blessed is the coming kingdom of our ancestor David” (Mark 11:10, NRSV)! The crowd that day saw Jesus’ procession as the second coming of the Warrior King David, who united the tribes of Israel and established Jerusalem as his capital city (2 Samuel 5-6). He too bore the titles “son of God,” “lord” and “savior.” He too came to bring “peace on earth.”

What Did Jesus’ Procession Mean?

As John Dominic Crossan and Marcus Borg write:

Jesus’s procession deliberately countered what was happening on the other side of the city. Pilate’s procession embodied the power, glory, and violence of the empire that ruled the world. Jesus’s procession embodied an alternative vision, the kingdom of God. This contrast—between the kingdom of God and the kingdom of Caesar—is central not only to the gospel of Mark, but to the story of Jesus and early Christianity.

The Last Week

Given this impossible to miss tension, how could Jerusalem not remain abuzz long past sundown on this Sunday night?

“Cleansing” the Temple

If tensions were not high enough already, the next morning, Jesus upped the ante. With footsteps that echo Simon Maccabaeus, Jesus first act following his procession takes him to the temple. While Simon restored traditional Jewish worship, Jesus flipped over tables.

While the meaning behind Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem was clear, those who witnessed his work in the Temple had questions. There was space for everyone in the Court of the Gentiles. The Law requires sacrifices and sacrifices require animals. Traveling long distances with animals for sacrifice is dangerous. It risks injury to the animal making them sacrificially unworthy. It is easier to buy them in Jerusalem. Buying animals requires the right currency. Money changing is necessary. So what is Jesus‘ objection? The only thing left is the exploitation and greed interwoven in the practice. The Temple conducts business using the tactics of Caesar that stand in opposition to the Kingdom of God.

Just as Jesus’ procession into Jerusalem the day before denounced how the State brought about peace, Jesus’ clearing of the Temple denounced a Church whose worship adopted the values of the State.

Give Unto Caesar

After two days of bold anti-institutional statements on the part of Jesus, the local institutional leaders come calling. First the chief priests, elders, and scribes explore the source of Jesus’ authority. Jesus response leaves them baffled. In the parable that follows, Jesus points out the greed driving their decision making.

Having failed, they tag in another set of establishment leaders, the Pharisees and Herodians. Here we finally get to “give unto Caesar what is Caesar’s.”

With this background, it is already clear that Jesus, whose actions upend both “Church” and State, is not offering a dismissive, “Let’s put faith in one box and politics in another.” But what does he mean?

Paying Taxes to Caesar

As I write this, it is early in tax season in the United States. Between now and mid-April we will all gather our income statements, identify deductible expenses, and either hand it all over to a tax professional or pump the information into some tax software. Based on our income and the taxes we paid during the year, we will either need to send more to the government or we will get a refund.

While it is natural for us to read the question about paying taxes to Caesar from this framework, it is not quite accurate. Rome did not tax the individuals in occupied nations. Rather, Rome taxed the nation as a whole. This left it up to local officials to determine how to gather the money to pay homage to Caesar. From that framework, the question being asked is really, “Should we as the Jewish people pay taxes to the nation occupying us?”

It is a brilliantly crafted question that intends to put Jesus in a no win situation. If he says yes, it undermines the meaning behind his entry into Jerusalem and would cause the crowd that the local authorities feared to abandon him for acting tough on Sunday but backing down when challenged on Tuesday. But if he says no, he is promoting rebellion against Caesar and the Jewish institution has reason to hand him over to the Romans for execution.

Give Unto Caesar (or God)

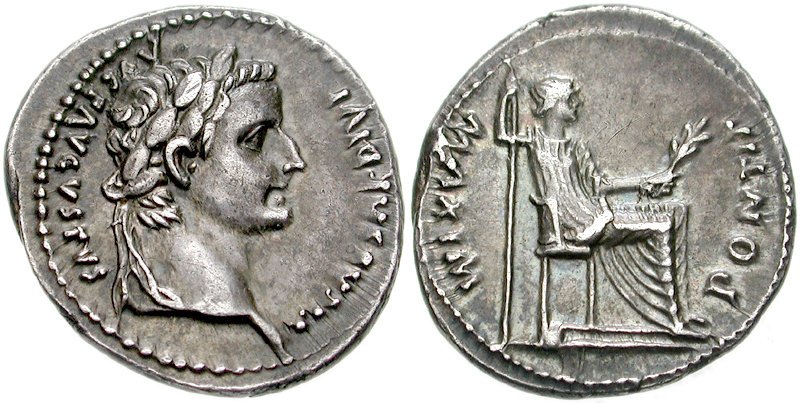

Instead, Jesus asks for a denarius, a coin equal to a day’s wage. What we as 21st Century readers do not realize is that there were two kinds of coins used in First Century Israel. The local coinage, which had no images on them, were commonly used by the Jewish people as a way to honor the 10 Commandments by not having graven images. The second coins, the official Roman currency, bore Caesar’s image and an inscription declaring him to be the divine son of God.

By simply having the coin, the institutional leaders lose the confrontation. They carry the coin with a graven image. As they stand there they commit idolatry. Their piety is undermined. Their allegiance is shown. They are one with the oppressor and opposed to the Kingdom of God. They have given themselves unto Caesar and they are Caesar’s.

Far from being an invitation to compartmentalization, Jesus’ response is an extension of his entry into Jerusalem. It is a declaration that you can only follow one Son of God. Each of us has to choose between the two radically different kingdoms they represent.

To give unto Caesar is to embrace power, glory, violence, and oppression. To give unto God is to follow the way of Jesus with his humility, grace, peace, and love.

The Gospel is a divine invitation for all of us to drop not only Caesar’s coins but his ideology. It is an invitation to embrace the way of Jesus.

Pingback:How We Get the Bible Wrong (including about women) - joeburnham.com

Pingback:Transformative Soul Care: From Discipline to Devotion - joeburnham.com

Pingback:When Love Feels Futile - Abundance Reconstructed

Pingback:A Better Question than, "Who sinned?" - joeburnham.com

Pingback:We are all a Spitting Image of the divine - joeburnham.com

Pingback:God calls people to Light Up the Darkness - joeburnham.com

Pingback:When Love Feels Futile - joeburnham.com